Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Listen here for Yusuf’s Story broadcast in 2006

Yusuf’s story is relatively simple: before 1967, Batir was in Jordan. After the Six Day War, it became part of Israel’s occupied territories. Until two years ago, Yusuf was able to move and work between Batir and Israel. Today, Batir is enclosed by the wall and Yusuf has to pass through tunnels and checkpoints to get to work.

A year and a half ago, in June 2006, I interviewed Yusuf (in Hebrew), wanting to hear his story and to hear what he and his villagers were sensing about the impending construction of the separation barrier. At that time, he was anxious about the path the wall would take and unsure what the as yet unknown details would mean for his family and the other villagers: he was dreading the feeling of imprisonment and the severing of his life from his land, his work and family and friends in Israel and the West Bank.

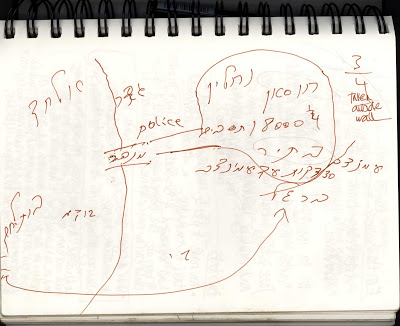

One year later, in July 2007, I met Yusuf again. By then, construction on the wall had begun around Batir and two other West Bank villages, enclosing approximately 18,000 villagers on one-quarter of the land that they had formerly occupied. The only entrance and exit now is through a tunnel and a checkpoint. He drew a map in my notebook to illustrate how the landscape and his life had been altered. It shows the wall around the village and the tunnel as the only exit into the world.

To what extent is the reality of the wall different from what Yusuf had imagined?

In his words:

Now we can see the new wall, where they are building the wall, the implications of how much it will limit us. We feel surrounded, we see the wall, we see how difficult it is, we see the dirt all around us and on us, we’re shut in, we can’t walk about freely, we can’t come and go. How difficult all this is.

This is not just a tunnel, not a regular tunnel. If anyone wants to visit us from somewhere else, they have to go through all sorts of controls and inspections, checkpoints This is the only way to get into Batir. You can’t come and go freely.

Since most of the villages’ agricultural land will now be on the other side of the wall, the villagers will have to go through checkpoints and gates in the wall to tend to their land. The only exit from the villages will be through a tunnel into Palestine. To enter Israel requires police inspection before the tunnel and another checkpoint inspection on the other side, along with a taxi ride. Before the wall was constructed, Yusuf told me, he walked for half an hour, breathing the fresh air, so close that he could see Aminadav, the Israeli village where he has worked for 18 years, from his house.

To arrive at his destination now means getting up two and a half hours earlier, going through inspections and checkpoints, waiting in the queue with hundreds of others, paying fifty shekels or ten dollars for taxi transportation, traveling 25 kilometers and then having to go through the whole thing again in the evening after work. “Two and a half or three hours. It’s a waste of my time”, he says indignantly, “this is no way to live.” He continues:

Everyone has to go to work. To get to Jerusalem, you first have to leave the village, then go through inspection at the tunnel, then enter the Palestinian Authority, then another checkpoint at Rachel’s tomb. Every day thousands are waiting in the queue, two hours, soon there will be two checkpoints.

Once the tunnel is completed, the only cars allowed through it and into Palestine, will be Palestinian. They will now be totally separated from Israeli traffic and the two peoples will no longer be able to see each other—except for the Israeli soldiers that Palestinians will see at checkpoints. If they want to enter Israel from, say, Bethlehem, they will have to go through additional checkpoints, similar to passport control.

The three-quarters of their land that now lies outside the wall, land the villagers had never agreed to sell, will become a mandatory sale to be negotiated with Israel. But, Yusuf says, it’s not financial compensation that preoccupies them. Rather, they grapple with how hard it’s going to be to live within the wall and without their land. He shakes his head as he tells me:

This is their livelihood and their only livelihood. They’ve always lived from this. They’re thinking about how to get their freedom so they can earn a living.

Yes, you might say, if life is so impossible, let them leave. But where should they go? What kind of work will they do? Other Arab countries are not exactly extending a hand of welcome. And once they leave, they may not be able to return.

Permission to work in Israel is granted only to men over 35 who are married with children but even this permission can be easily and capriciously withdrawn. Life has become not only harsh but unpredictable and precarious.

A year ago, Yusuf could not understand how it had come to this. What has he done to create this situation? What has he done wrong? Why are they all being punished? It is unfathomable.

A year ago, he questioned the rationale of collective punishment and punishment that seemed in no way to fit the crime. “It is hard and bitter for me to leave my birthplace, I’ve built my life here,” he says and I tell him is very hard for me to listen to his story.

Today, his voice rising in anger again, Yusuf is uncomprehending at the injustice that is dismantling his life. In his frustration, he addresses Israel through my recorder:

You can get yourself a stronger army, do something else powerful, I don’t know what. You have cameras, you can see everything these days. You don’t need to come over here and lock me up in my house. If you’re afraid of us, why not build a wall around your house instead of around mine? Why do you take my land away? Before, you had suicide bombers, now you have rockets. What have you gained?