With love and in memory of Midge. Requiescat in pace. We miss you a lot.

This is a personal story, based on conversations with my school friends from a very far away place and a very long ago time. Midge, Pat and I were children together at Woodstock, an international boarding school in Mussoorie in the state of Uttarakhand, 6,600 ft up in the Indian Himalayas, while our parents lived in India, Pakistan or other countries.

We didn’t know we were third culture kids until a few years ago in a presentation at a school reunion we were introduced to the work of two sociologists, David Pollock and Ruth van Reken, through their book “Third Culture Kids.” The audience erupted into a series of “ah-ha’s”, giggles and whispers. “So that’s who we are,” a woman said, smiling, nodding her head. Her spouse grumbled: “So that’s why you’re like that.” For us in the audience, everything fell into place: now we had a name, now we could recognize ourselves and each other.

We didn’t know we were third culture kids until a few years ago in a presentation at a school reunion we were introduced to the work of two sociologists, David Pollock and Ruth van Reken, through their book “Third Culture Kids.” The audience erupted into a series of “ah-ha’s”, giggles and whispers. “So that’s who we are,” a woman said, smiling, nodding her head. Her spouse grumbled: “So that’s why you’re like that.” For us in the audience, everything fell into place: now we had a name, now we could recognize ourselves and each other.The second culture was where we actually grew up–in this case, India. The third culture was an interstitial culture, the culture that grew up between the first and second cultures and the one that we inhabited. Although my friends were mishkids, the children of missionaries, other parents worked in the diplomatic or military services or in the business sector.

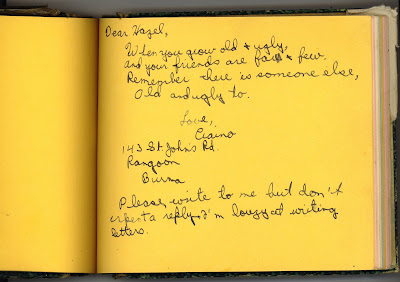

This third culture is highly mobile: its people are always coming and going, their lives marked by arrivals and departures, creating a child and teenager who become skilled at developing relationships.

If you are a third culture kid, you might jump into a new relationship quickly and deeply, with an urgency born of knowing the next move is always on the horizon. Or, you might prefer a casual, superficial friendship, shying away from closeness because you already anticipate the loss as departure time looms.

If you are a third culture kid, you might feel “wrong” or out of place a lot of the time, not knowing the ropes, because you are always learning a new culture, including your home culture. Returning to America from India, my friends remember how they did not understand its popular culture, its slang and social rules, how things work, what was expected of them. Because they looked like everyone else in their home town, they were expected to behave the same too, even though they thought and felt quite differently. They felt “other” but didn’t look it.

If you are a third culture kid, you might feel “wrong” or out of place a lot of the time, not knowing the ropes, because you are always learning a new culture, including your home culture. Returning to America from India, my friends remember how they did not understand its popular culture, its slang and social rules, how things work, what was expected of them. Because they looked like everyone else in their home town, they were expected to behave the same too, even though they thought and felt quite differently. They felt “other” but didn’t look it.

At the same time, in India, they looked “other” but did not feel fit, leaving them confused when their second culture responded to them as though were foreigners or strangers. Feeling different wherever they are, third culture kids tell their childhood stories not realizing they may come off as arrogant or boastful to those who don’t come from a third culture.

Given this strong but sometimes murky identity, one can understand why my classmates and I have a strong attachment to our past and to each other, with connections that last for decades and that assert themselves with special strength at school reunions. You can hear us confess that other third culture kids are the only ones who “get it” and are therefore the only ones among whom we can feel truly at home. It takes one to know one; it’s a precious and enduring recognition.

The mobile third culture child can grow into a restless global nomad adult, unable to escape the need to be on the move, to always have another place in mind which can be very disconcerting to other members of our families. I call this place elsewhere.

Mobility, restlessness, a certain detachment–and it’s no surprise that some third culture kids harbor an eccentric view of home and an odd way of describing what home means to them. In his book, Paper Airplanes in the Himalayas: The Unfinished Path Home, Paul Seaman describes what home meant to him, growing up in Pakistan:

Like nomads, we moved with the seasons. Four times a year we packed up and moved to, or back to, another temporary home. We learned early that ‘home’ was an ambiguous concept, and, wherever we lived, some essential part of our lives was always someplace else.

You can hear Midge, Pat and me talk about what “home” means to us, along with fragments of wonderful Indian music.

******************

“There’s No Such Place As Home” was broadcast on WPKN on February 10, 2010.